Two things happened recently that made me pay attention to wearable tech and the idea of the quantified self, and how both highlights how tech culture is getting it wrong.

The first was over lunch when I saw a senior manager plug her Fitbit into her iPhone and sync up her data. I cheekily asked her what it did, and she told me it told her how many steps she had taken and show she had slept. I responded that I always knew how well I had slept by the way I felt when I woke up. She didn’t disagree, but the Fitbit was a habit, and she was committed.

The second was when a non-tech colleague showed me his new Pebble watch. He proudly told me that he knew his phone was ringing by looking at his watch, only to fumble around to find his phone when it rang a few moments later.

The Quantified Self and wearable tech have been hot for a while now. Devices and apps can now help us see what’s on my phone, show how far I’ve run or how many steps I’ve taken, let me know if I am sleepy or if I slept well, tell me if I am standing up straight and tall or slouching, tell me if my heart is still beating, if I’m still breathing, or if a recent Indigogo campaign is to be believed it can also measure your calorie intake (Pando.com reckon that the calorie measurement device was most likely a total fraud). Currently there are over 200 wearable tech devices in the market with 130 in the “lifestyle” category. To put this in context, there are a handful of start-ups working to end global poverty, and over 2 billion people living on under $2 per day.

The promise of the quantified self is that self-knowledge can be attained through the tracking of personal data. All the devices and apps playing in the quantified self space usefully record and analyse multiple data points which are then attractively presented to the wearer/data-subject when the sample size is large enough to present a trustworthy result. The quantified self appeals to middle-class anxiety about perfection, purity, and significance. In a world where the self is subsumed by corporate structures, governments, banks, insurance companies, and media, the quantified self is a way of being reassured that you matter, that you’re important, that your life has meaning.

The most popular quantified self device is the Fitbit ($66M funding), who make a range of devices that attach to clothing or a part of your body, and track movement, sleep, eating patterns, and other data. The Fitbit website says, “The Fitbit family motivates you to stay active, live better, and reach your goals.”Fitbit also includes some pretty impressive dashboards for visualising all that personal data, and some nifty badges like the daily climb, astronaut, or stair climb to help keep motivating their users. Look mum, I got a new badge!

Samsung recently announced the Gear fit, an update to the Samsung Galaxy Gear watch released last year to mixed reviews. A Samsung spokesman said in a press release for the Gear Fit that (emphasis mine)

“[O]ur Gear product portfolio continues to expand with unique devices for a wide range of lifestyles, including the new Gear Fit designed to help those consumers striving to live more fit and active lives without sacrificing their own personal style or their ability to stay connected on the go.”

This confirms the merging of fashion, fitness, and technology evident in the quantified self and wearable tech craze. If “Fashion is the armor to survive the reality of everyday life” as photographer Bill Cunningham puts it, then wearable tech devices are here to stay and will become even more tightly fused into our lives, and the trail of data we leave behind us. And it is the data trail which has concerned some privacy advocates, including uncertainty about who owns the data generated by the devices – the wearer/data subject, or the business generating the pretty graphs. This becomes concerning when you consider a wearable tech business could make a lot of money selling personal data to health and life insurance companies, or agencies responsible for vetting potential employees. In this context wearable tech is more of an enabler of the compromised self rather than the quantified self. (There is an excellent summary about some of the privacy concerns here)

The quantified self is another example of an obsession with libertarian individuality that seems to proliferate in tech culture. It sees the individual as sick, flawed, in desperate need of a digital confessional, but ultimately perfectible. Through the peculiar intimacy of a wearable device that the individual is re-imagined as a hero, as an obedient subject to data. That technology can be employed to improve the health and well-being of both individuals and communities is without question, science is full of examples where science and technology have been game changers on a global scale.

What concerns me is that the finest minds of our generation are making toys to support narcissistic behaviour rather than curing world hunger.

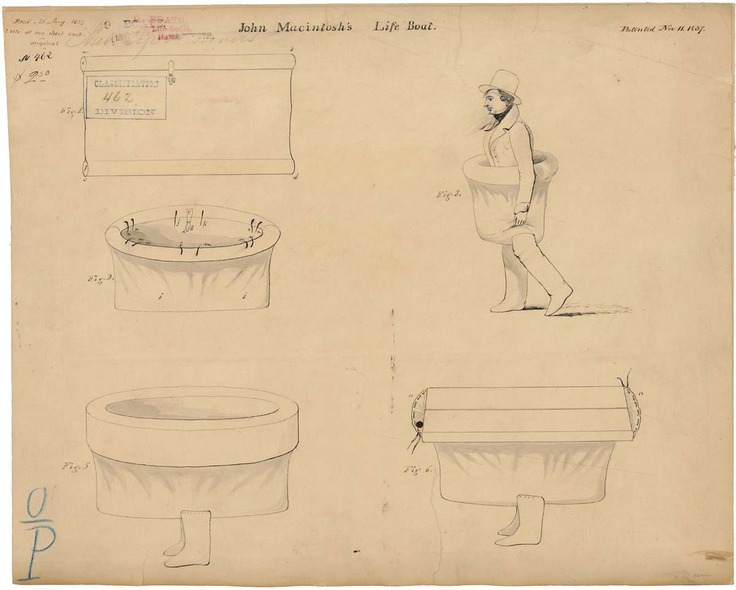

Fabulous image sourced from wearable-technology.co